The Enigmatic Allure of Holy Motors

Twice viewed, yet perpetually pondered, ‘Holy Motors’ leaves us questioning the source of the pleasure it indubitably delivers to its audience. This pleasure surely transcends nostalgic homage—despite assertions heard across the Cannes corridors—and its essence lies deeper than cinephile sentiment. We sense ourselves as the illegitimate offspring of cinema, arriving too late to a world no longer belonging to us nor understood in the same manner. Therefore, there is a perverse delight in witnessing the disarray of luxury—the most expensive underwear tossed aside, a violation perceived within the most opulent chambers. Our pleasure stems from the destructive undercurrent harbored in each of the protagonist’s assignments, his heretical vigor, which retains cinematic purity in every frame—a conviction ardently upheld by Carax, akin to Murnau’s camp, rather than Tsai Ming-liang’s ‘Visage,’ which dared to cross that threshold, at the cost of being metaphorically hanged.

Carax’s Cinematic Odyssey

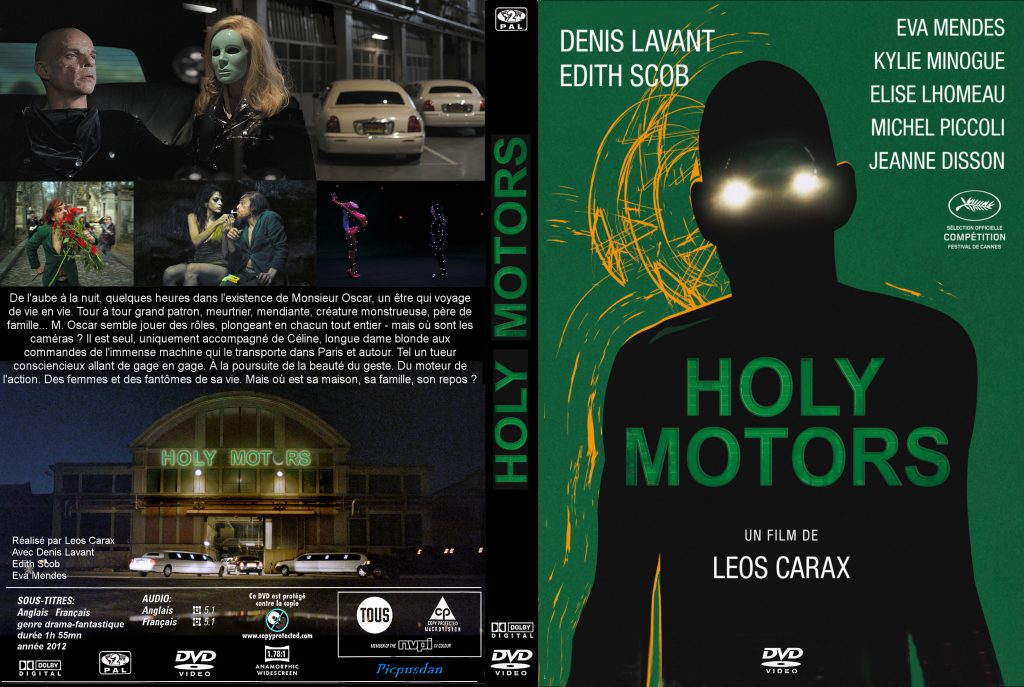

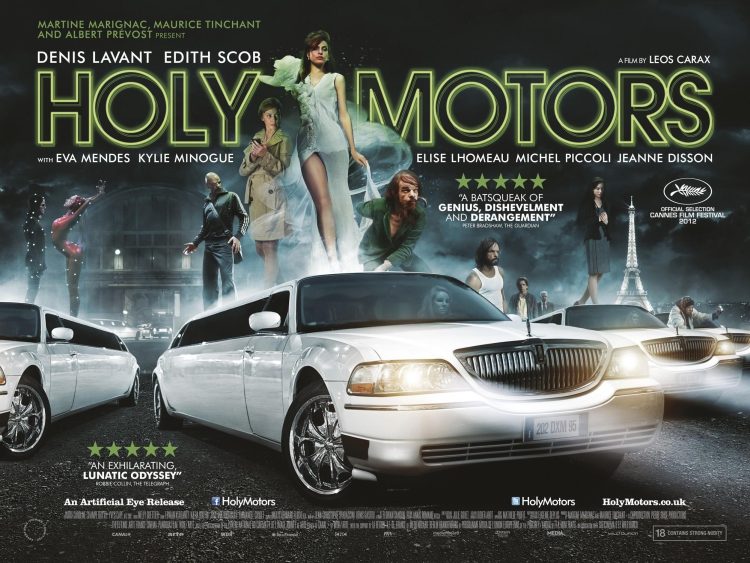

‘Holy Motors’ manifests as Léos Carax’s own ‘De la guerre,’ embodied by a character carrying the director’s namesake, Monsieur Oscar—Carax himself being an anagram of Alex Oscar. He traverses life phases like stages in a video game, each requiring success to advance. The struggles depicted within these vignettes symbolize the pursuit of happines—within Bonello’s context—or the battle to make a cineaste’s film, as with Carax. Oscar tirelessly performs diverse roles, meticulously preparing within a limousine that courses through Paris under the stewardship of Edith Scob, reminiscent of the bygone struggles movies faced during their development, particularly in securing CNC funding.

The Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Cinema

‘Holy Motors’ stands as a must-endorse cinematic project in France, representing every facet of today’s ‘art-house’ cinema, tackled with irreverent reverence by Carax. From the intimate portrayal of society (Oscar as an aged foreign beggar in Paris) to action-packed episodes with flashy American aesthetics (Oscar as an east-end assassin), reflections on self-portraiture (Oscar wrestling personal issues as a Carax doppelgänger), to avant-garde digital animation sessions, Carax ingeniously synthesizes these diverse genres, including the obligatory musical interlude inserted for ‘vitality.’ The presence of M. Merde, a nod to Carax’s multi-director short film projects, adds another layer to this complex cinematic concoction.

The Narrowing Gap Between Construct and Reality

A pivotal device in ‘Holy Motors’ is the gradual blurring of tasks’ boundaries. Initially marked by comical ellipses that return us to the limousine, its contents increasingly penetrate these transitions, challenging perceptions of fiction versus reality. These moments, where reality seemingly seizes Oscar, raise the specter of Carax ventriloquizing his own persona through the character. When confronted by his enigmatic producer—portrayed by Michel Piccoli—Oscar’s dialogue delivers a profundity on the nature of filmed art:

“At first, cameras were heavier than us. Then they got smaller than our heads. Now, they are invisible.”

The conversation escalates from a lament over lost theater to an embrace of cinema’s evolving ethos, contemplating its relevance and survival in a society saturated with unobserved images.

Narrative Tragedy and Cinematic Rebirth

‘Oscar’ as a cinematic being, eternally performed and trapped in his role like Chaplin’s factory worker, tangentially aligns with Carax’s own trajectory. It is a cinematic tragedy when the images, ubiquitous and overlooked, compel Carax, the former luminary, to be the ‘good boy,’ passing each trial while resonating a ‘Fuck The Universe’ defiance—a sentiment perhaps amplified by contemporary contexts. In an electrifying sequence, Oscar, masked and ready for action on the Champs-Élysées, halts his limousine, leading us to surmise a confrontation with Nicolas Sarkozy as his probable target—an event that metaphorically confronts five years of ‘Sarkozyst cinema.’

Holy Motors: A Delicate Balancing Act

The delicate balance that ‘Holy Motors’ maintains—between irreverence and reverence, humor and ego—informs its unique narrative fabric. Carax recaptures the heart of the film and the essence of beauty, parodying the feigned dreamers that followed in his footsteps, simultaneously evoking emotion and laughter.

The Cinephilic Pilgrimage and the Need for Heresy

The film commences with Godardian flair, invoking Marey in the credit sequence before Carax either awakens or ventures into a dreamlike state. He enters an auditorium of specter-like spectators, implying a cinema that may have taught us errors about the shadow play of existence. Truffaut once likened cinephilia to attending mass, whereas festivals resembled the passing of the Popemobile—a specter of former belief. It is in this context that heretics are invaluable, mirroring the film’s concluding notion that the thirst for cinematic ‘engines’ and ‘action’ has waned.

Discussion about this post